Devamlılık İçin Kamera Pozisyonları

noun 1. the unbroken and consistent existence or operation of something over time.

2. the maintenance of continuous action and self-consistent detail in the various scenes of a film or broadcast.”a continuity error”

The 180 degrees rule is probably the most commonly taught guideline aimed at assisting filmmakers in maintaining continuity on screen. It suggests to organize the positioning of the cameras on one side of an imaginary line running through the space of the scene dividing it in two, the line or axis of action. The idea is to avoid for multiple angles to confuse the audience understanding of the spatial relationships when cut together. We avoid’ jumpy’ feelings when moving the audience from one perspective to another and deliver an easy to follow representation of the world through multiple two-dimensional frames.

Thanks to FilmmakerIQ for that quick explanation.

And, Film Riot for this one.

When preparing a scene, we often aim to maintain what editor Walter Murch calls the eye-trace, the 2-dimensional place and the 3-dimensional space. Does the cut pay respect to the location and movement of the audience’s focus of interest within the frame? Is the cut true to the 2D representation of the film world? Is the cut true to the physical/spatial relationships within the scene? These are NOT the most important aspect of editing a scene but when ‘respected’ they will help the audience follow the action and suspend disbelief.

For some, the line of action can become an obsession. For example, some could believe that in Western Cinema, due to the nature of our left-to-right writing, characters driving the action should be on the left of the screen and character receiving the action should be on the right, that progression should be a left-to-right movement and the opposite should mark a return. A bit extreme, but interesting nonetheless. The line should not be an obsession, it should be a friend. If continuity, as opposed to disorientation, is what you seek. There are a few techniques that will allow you to cross the line without loosing the impression of continuity by avoiding to create jump cuts.

- Placing the camera on the line of action, as a POV (Point of view) shot will allow us to use that angle as a transition between the two sides of the line. Moving the eyeline, the person in the shot pans his/her head, will suggest what side of the line we will cut to.

- The camera can cross the line of action during the shot. The audience is now aware that we are on the other side of the line and that the spatial relationship have changed. When editing, the shot from one side of the line can be joined with a shot from the other side of the line if we insert the “camera crossing the line” option in-between.

- The characters move from one position to a another, hence moving the line. The camera crosses the line not because it is moving, but because the line moves across the camera’s field of view. This shot can be used as a bridge between one side and the other of the initial line of action.

- The use of cutaways,an interruption of a continuously filmed action by inserting a view of something else, usually a close-up or an extreme close up of an object, will allow us to jump to an new interpretation of the line of action.

These methods allow you to reshape the staging of the scene, and that is great. The question that not many people ask is: why? Why would I change the staging of a scene halfway through it? Russian actor/director Constantin Stanislavski believed that each scene in a play could be divided into units of action. In each unit of action, each character has a sub-objective and its actions help them to achieve this goal. One important aspect of his now famous System is the identification of the various “beats” and how they are arranged to form the charactersʼ progression throughout the plot or scene.

When discussing visual script breakdowns, Steven D Katz highlights how identifying the ‘beats’ that constitute a scene is one of the first task the director should include in his process. By crossing the line of action you are changing the audience perspective and the representation of the content of the scene. These changes can help you adapting to ‘needs’ of the various beats.

Let us look at a few examples (spoilers ahead, it’s an analysis): Avatar (2009, Dir. James Cameron. Fox) Stray Dog (1949, Dir. Akira Kurosawa, Toho) Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005, Dir. George Lucas, Fox) Jaws (1975, Dir. Steven Spielberg, Universal) Pulp Fiction (1994, Dir. Quentin Tarantino. Miramax) The Shining (1980, Stanley Kubrick. Warner Bros.) In these examples we can seen how crossing the line while maintaining continuity can be achieved in various ways. Most importantly we can seen how these ‘crossings’ tend to happen at key moments within scenes, breaking the content in various ‘beats’. This separations break down the various objectives, driving forces and twists within single scenes thus guiding the audience understanding of it all. Avatar (2009, Dir. James Cameron. Fox)

In this case, we could argue that crossing the line just before releasing the arrow announced a twist of fate within the fight. Neytiri reverses the situation and takes the upper hand. Then, when placing us on the line the second time, Miles fate is kept hanging before bringing the audience back to the initial perspective. The line was crossed to play with a reversal of power.

7. Neytiri is left of frame. We see the arrow from left to right. Miles is now right of frame as we have crossed the line.

Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005, Dir. George Lucas, Fox) Jaws (1975, Dir. Steven Spielberg, Universal) Pulp Fiction (1994, Dir. Quentin Tarantino. Miramax) The Shining (1980, Stanley Kubrick. Warner Bros.) Stray Dog (1949, Dir. Akira Kurosawa, Toho)

In this case, we first jump the line by using a cutaway. The pause invites us to wonder as to the effect the gunshot had on Murakami. We come back to the line from a new angle, inviting the audience to rediscover the scene. The final crossing of the line reaffirms the reversal of power within the scene. Even though White shot Murakami, the latter is now chasing him.

1. We start with Murakami (left of frame) being held at gun point by a man I am going to label as White (right of frame)

7. We come back to Murakami (now to the right) and White (to the left). We have crossed the line but the previous shot had taken us away from the line and the edit feels continuous.

10. Murakami’s anger. We are almost on the line. Murakami’s eyes are aiming left, suggesting he is to the right.

23′. Murakami moves forward (right to left). White (left) runs towards the camera and to the centre of the frame.

23″. White’s face blocks Murakami. We are now on the line of action. In the next shot we can move either side of the line.

Avatar (2009, Dir. James Cameron. Fox) Jaws (1975, Dir. Steven Spielberg, Universal) Pulp Fiction (1994, Dir. Quentin Tarantino. Miramax) The Shining (1980, Stanley Kubrick. Warner Bros.) Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005, Dir. George Lucas, Fox)

In this case, we could argue that the initial positioning favours Palpatine as he guides Anakin through the conversation. Anakin moves the line of action, changing the staging, only after hearing mention of the dark side. Anakin’s question guide the following part of the scene. Palpatine’s argument become more insisting and this is emphasised by having him circle around Anakin not once but twice. Repeatedly moving the line (and adding a jump) creates a slight feeling of disorientation but maintains an overall sense of continuity of space and time.

2. They continue to walk together. Palatine is slightly to the left of Anakin. The line of action is between the two of them.

10′. Here we have jumped the line. Palatine is suddenly to the right of the frame and Anakin to the left. This jump in addition to the circling motion of the actors feels slightly disorientating.

10″. Palpatine moves across the field of view from right to left thus moving the line of action. This repeat adds to the circling feeling and further supports a feeling of disorientation.

Avatar (2009, Dir. James Cameron. Fox) Stray Dog (1949, Dir. Akira Kurosawa, Toho) Pulp Fiction (1994, Dir. Quentin Tarantino. Miramax) The Shining (1980, Stanley Kubrick. Warner Bros.) Jaws (1975, Dir. Steven Spielberg, Universal)

In this case, the line of action is respected for most of the action. It is a simple beat between a Man and his Kid. The line is only crossed to break away from this simple moment and move back to the plot (you know the killer shark and all…)

15′. We are now on the other side of the Brody-Kid line. It feels continuous due to the previous ‘neutral’ shot of Ellen.

15″. Kid (left) walks away leaving Brody (right alone). The line between them vanishes. Off-screen sound suggests a new line of action.

16. Brody is now left of frame. Continuity is maintained and a new line between him and his background his established.

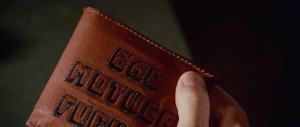

Avatar (2009, Dir. James Cameron. Fox) Stray Dog (1949, Dir. Akira Kurosawa, Toho) Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005, Dir. George Lucas, Fox) The Shining (1980, Stanley Kubrick. Warner Bros.) Pulp Fiction (1994, Dir. Quentin Tarantino. Miramax)

In this case, we could argue that once the geography of a static scene has been established the line of action becomes less important. The jump can still add a bit of ‘discomfort’ to some transitions, in this case Yolanda’s agitation is supported by repeatedly jumping the line of action between her and Jules.

1. We start with a master with Jules (left) holding Ringo (centre) at gun point and Yolanda (right) aiming for him in the back.

10. We have jumped the line of action. Ringo is now to the left and Jules to the right. To me, this jump does not break continuity that much. Why? Well, by now we, the audience, have gotten used to the geography of the scene. We clearly know from the master and close ups where everyone is. Nobody is moving, we can still follow. This shot also announces a fourth character is about to enter the scene.

11. Back to Yolanda (right) as she moves. We have jumped the line between her and Jules. The jump, adding to the movement, signals a disruption.

15. We keep jumping the line. It adds to the agitation of the character and does not disrupt continuity much.

Avatar (2009, Dir. James Cameron. Fox) Stray Dog (1949, Dir. Akira Kurosawa, Toho) Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005, Dir. George Lucas, Fox) Jaws (1975, Dir. Steven Spielberg, Universal) The Shining (1980, Stanley Kubrick. Warner Bros.)

This scene from the Shining is one of the most popular example of what can happen when we break continuity intentionally. It can help us play with the audience and create an odd sensation, when needed. If you insist in calling it a rule (of 180 degrees), it has to be known in order for it to be broken effectively.

Yorumlar

Yorum Gönder